Giorgi Xaniashvili’s art is most likely to shock the Georgian audience,

even if the artist does not see it as his ultimate goal. The society where

religion is as prevalent as it is in here, finds it hard to accept the harsh

truth of Xaniashvili’s art.

‘I am not trying to preach moral codes; I just

don’t like the influences and attitudes that are dominant in today’s society. I

find them comical.The

values that are wrapped in a way that is appealing to the society and that they

cherish, whereas in reality it turns out that the Kinto is a homosexual and the

society does not want to believe in it, they like the dance so they ignore it.

My aim is to declare the situation, present it

in its most extreme form- so that it becomes more visible and leaves no one

indifferent.’Declaring no interest for the Nature-mortes that seem to flood Georgian

art, he still sees the place for the subject matter.

Xaniashvili’s art does share feminist thought protesting against the

objectification of women and their apprehension as one’s property. In a society

where female solidarity is non-existent it is astonishing to find a male artist

thinking in this way. Protesting against the gender stereotypes, he realises

the depth of these implications, trying to distance himself, he catches these

influences in his thinking too.The artist continues the theme of masculinity and boldly criticises our

perception of a ‘successful man’- with an expensive car, donating money to the

church and owning a woman.

Working in comics continuum, Khaniashvili builds the narratives around

the subjects such as the fetishizing of boys. Having a baby boy is still seen

as one of the great achievements of a woman- a boy as a future of the name, the

genetics, the family and the tradition.

The cartoon culminates in the son having oral sex with the father,

cutting deep into and pointing at the paranoia of the society. For a country

with an appalling rate of gender-specific abortion (when the mother decides to

abort the pregnancy in case of having a girl) it is vital to highlight the

absurdity of the situation.

Nowadays, the subject of homosexuality is one of the most debated issues

in Georgia. Xanianshvili decided to summarise the society’s perception of

these people-notably portraying the main hero as a man, as in Georgia

homosexuality is almost always associated with men (the anxiety towards the

male sexuality and even in here women are omitted) with the rabbit ears, the

priest on the other hand is trying to protect his carrots and chases the rabbit

away.

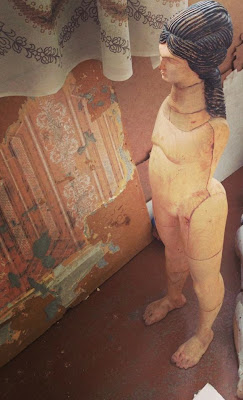

All of his drawings act as sketches for the sculptures either in wood or

plaster. His future plans are to create the series of pseudo-decorative multicoloured

porcelain sculptures, which will resemble the ones the soviet housewives have

been obsessed with, but with an ironical twist so characteristic to the artist.

The gay rabbit with a mobster priest are already in plaster waiting to be

painted.

Khaniashvili works a lot with the material of wood; preferring it for

its adaptable quality, the artist exploits the material creating the headless

animals connected to each other as a symbol of the human

interconnectedness. His most mature work so far is also in wood; the duo of a Venus and an

Archangel offers a coexistence of the mythological and the contemporary, dead

and very alive, mobile and static, flexible and rigid.

When working on the iconography of a Venus, the artist draws parallels

to the figure of the Christ: ‘in the nutshell, Christ is also a mythological

figure, but in comparison to Venus, this mythological figure is still alive and

has not lost his relevance.' The goddess Venus is dead, but still personifying

the module of beauty; Xaniashvili’s Venus tries to capture our contemporary

perceptions of beauty and perfection. The hybrid of the goddess and the

near-to-anorexia body tell so much of today’s society.

In our religion, the archangel is never depicted in 3-dimensions; the

chronological development of the Orthodox Christianity seems to be the motive

of the work. The figure of the archangel creates a contrast to the one of the

Venus; the Goddess’s body follows the anatomical build up of a human, whereas

the archangel’s body is smooth and sexless, even the joints are immobile. The

heads of both sculptures are quite precise copies of the more known

iconography, Xaniashvili creates the gods and saints of XXI century if you

like.

Ironically enough the artist often gets commissions from the Church; for

example a statue for the Catholic Church of Tbilisi. Then he creates cartoons

about his working process. The main agenda is the objectification of something

sacred, which equates to scandal in a society of Tbilisi; it is not surprising

that the Facebook comments are often disapproving. It is peculiar how Xaniashvili and many of his contemporaries use Facebook as their online

galleries, acting like the agents of themselves; you can view their art, contact

them and even buy it from Facebook. For Xaniashvili religion is an object and

funny enough a way of income. The climax of such relationship takes place on

the last part of the comics; after taking the money for the work, the artist

kisses the cross- ‘paying the dues’ as he calls it.

He analyses the religion coming out of the everyday context, how

religion intervenes and is intertwined with the everyday living in Georgia,

rather than criticising the religion itself, Xaniashvili claims to criticise

these influences. The grim and grotesque imagery does translate the everyday living into art with the anatomical precision, no aestheticism involved.

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/giorgi.xaniashvili?fref=ts